Before I get into talking about Zach Cregger's 2025 horror film Weapons itself, I should be up front about my biases. When I first heard that Cregger was beginning work on it, something jumped out at me. Me, specifically. It was described as an, "interrelated, multistory horror epic that tonally is in the vein of Magnolia." Magnolia being the Paul Thomas Anderson film that's my go-to answer for the unanswerable, "What is your favorite movie?" question. Magnolia being the inspiration for one of my tattoos. Magnolia being the film this very blog's title is a reference to.

What I'm saying is that I came into Weapons being told that it was heavily influenced by one of my most treasured and important films, and there is no way to separate how Cregger handles those influences from my reaction to his work. That said, this is not a piece about the ways that Cregger's work is in conversation with Anderson's, at least not directly. But when I say I loved this movie, you should know that I was moved by the same work that clearly moved Cregger.

That said, let's talk about what Weapons is, what Weapons is not, and being careful not to analyze a film's handling of a metaphor that it's not deploying in the first place. I'll avoid spoiling as much as I can, but if you want to see the film totally fresh, I'd recommend not reading.

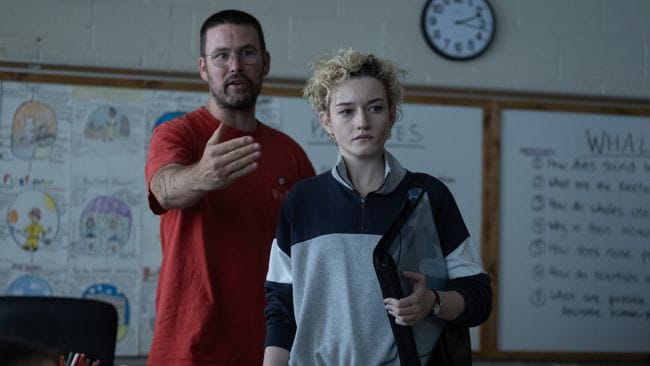

Weapons tells the story of a suburban town dealing with the sudden and inexplicable loss of 17 children. All of the children attended the same class, that of Julia Garner's Justine, and only one child in the class did not disappear: Cary Christopher's Alex. All of the children, at exactly 2:17 am, woke up, walked out the door, and ran into the night. No one knows why the left, where they went, and who might be involved.

Structurally – and this is one place where Magnolia is an influence but not a straightjacket – it's broken up into multiple stories, each following a different character as their paths overlap. Cregger's script also plays with chronology, picking up and setting down each story at different points in the timeline. In that respect, it's more like a 90s Tarantino film, and it's one of the few movies I've seen that understand how to use that structure as a vital part of how the story is told and not simply as an affect.

We get to see the many overlapping and conflicting ways the loss of the children has affected the town, from grieving parents to their traumatized teacher to the cops failing to make any headway on the disappearance. Through every step, pieces fall into place for us in the audience, as we begin to understand both what happened and why.

That's the story of Weapons. But what is Weapons actually about?

If you've kept up with reviews and discourse, you might have picked up a growing belief that Cregger is using this story as a metaphor for school shootings. There are, after all, a number of children, now gone. There's a single survivor in the class, and a teacher who some see as a potential bad influence on all of them. There's also a moment where a character sees a vision of a giant assault rifle in the sky. If you've seen this view gain steam, you might also have seen that many people think Weapons does an extremely bad job of handling this metaphor. There's a problem with this, though: the film is neither by intent nor via its text about school shootings.

Critical analysis of a film's handling of things it is not actually engaging in is nothing new. Letterboxd is a great site in a lot of ways, but its social media-esque popularity system of likes allows controversial and hyperbolic reviews to float to the top of the pile whether they're saying things that make sense or not. This has only accelerated the frustrating trends of trope hunting and contextless cultural critique that grew out of the necessary critical work of breaking down these tropes in the 2010s. It was good to discuss where tropes come from, where they've been thoughtlessly overused, and how to move past them. It's been less good since that shifted into more simplistic, "I found a trope!" approaches to critique have become a reliable way to farm hate clicks and virality.

Pulling themes and metaphors out of a film that were not intentionally present is a valid way to discuss art. A film's text and subtext as built by an artist can be out of sync with what the content adds up to. We are also people with individual experiences who can and should read things in a different way than the artist themselves. Saying that Weapons brought up emotions and thoughts about school shootings in you doesn't require that the film or artist's intent to agree with you.

It's the step further, the one where your personal read becomes the criteria for weighing whether the film was successful or not, that gets dicey. Intent isn't everything in art, but it's also not nothing. Art does have a text, and fairly and accurately identifying what that text is should not be seen as optional in critique. If a work doesn't textually back your personal read up, negotiating through that divide is what critique and analysis is. A read of a film, in other words, can be both valid and incorrect textually.

Let's start with Cregger himself, who's been very up front with what was on his mind when he made Weapons. “I was working on postproduction on Barbarian when my best friend died very suddenly in a really awful accident,” he told Rolling Stone.

In an effort to deal with his grief, Cregger begin “a blitz of writing, over about two weeks or so… I just started, sentence one: ‘This is a true story. Half of my hometown, all of these kids bailed.’ You know, I’m writing this cold open, and I don’t know where the kids went. I’m just like, ‘OK, let’s go. Let’s see if I can solve this. What happened? Who were they? What was left behind? What does it feel like?’”

The inciting moment for this script was a tragedy, but not a murder. It was an accident, and not even of a child. As the script developed, other personal strands wove themselves into the narrative.

And in writing the section told from the perspective of Alex, the one third-grader who doesn’t go missing, Cregger says he tapped directly into his own past. “That is straight-up, like — I lived that chapter as a kid,” he admits. “Again, I don’t know if people need to know this going in, but… it’s very much what it’s like to have a parent who’s an addict, and the child has to become the caretaker as this sort of foreign thing comes in, and…” The look of horror is back. “I’ll leave it at that.”

Every interview Cregger has given underlines how personal the undercurrents of his film are, and that none of those undercurrents arose from school shootings. Certainly, a school shooting is one of the tragedies a community can face, and given our cultural moment, thinking about it while you watch is reasonable and maybe even expected. The thing about art, though, is that while it's in conversation with culture, it also isn't required to address every possible interpretation that could arise from it. An artist should be thoughtful about how audiences might read a work, but that can't be a priority when focusing on something deeply personal.

What I'm saying is that you can critique a film for how it engages with topics that could read differently than intended, but you need to be clear that's what you're doing. That the film isn't doing a thing, but walking on ground where that thing is going to come up for audiences. Even then, building an argument in support of that take needs to take more into account than the critic's own subjective experience. At minimum, you should always be asking yourself, "Is this me, or is this the film?" The beauty of art is that it can be many things to many people. Grappling with what a film did to you is different than what the film actually did, and you can talk about either, or both, without pretending the other doesn't exist or matter.

It's the exegesis vs. eisegesis problem that comes up in religious analysis: identifying when you are pulling from the text and when you are bringing something to it is critical to honest discussion.

When we – that would be my wife and I – came out of the theater and started talking about Weapons, the common school shooting interpretation came up. Neither of us saw anything meaningful in the text of the film about that. In fact, our biggest takeaway at first was just that it seemed intentionally built to be, first and foremost, a good, enjoyable movie. Reading interviews later, Cregger backs this up when raising the film's themes around grief: "I don’t care if anybody gets any of that when they watch it. I want them to have fun. If the story rips, none of that matters."

As we kept digging in, though, the film's actual interests seemed clear. It cared about the ways institutions are insufficient in helping children and the larger community. How those same institutions punish people who overstep their defined role out of concern for those under their care. The ways those same institutions protect bad actors from harm when it serves their interests. There were also recurring themes of addiction, of abuse, of enforced silence.

What wasn't in the film were threads that mapped to a specific tragedy like school shootings. Much of the trauma gripping the community arose from a lack of resolution. There were no bodies to bury, nor any villain to disdain. As time passed and lack of progress was made by the authorities, the community's need to find someone to punish became overriding. The surviving child was explicitly not portrayed as anything like a school shooter. He wasn't angry at his bullies, or at anyone, really. The tragedy didn't even happen at the school, but across over a dozen individual homes.

My problem with the heavy focus on a single kind of tragedy is it actually diminishes the film's ambitions and crushes down its themes. Cregger doesn't seem interested in handing us a single, unifying theme. One of the ways it's most spiritually aligned with Magnolia is that it's about how separate, individual traumas collide with each other under pressure. The diffuseness of its characters' experience is the point of a story like this. In interpreting a story structured the way Weapons is, denying the multiplicity of experiences in it is to ignore everything essential about the work itself.

It's disappointing to see so many take a film about the spidering fractures caused by a shared tragedy and force it into a tiny box in which they can go hunting for tropes. In a time where mass market art is increasingly studio-managed and depersonalized, why contort oneself so much to treat a personal and ambitious film as a simple allegory? And then punish it for failing to portray that allegory to your satisfaction?

I can't say whether Weapons will be for you, and I won't say there are not many good ways to approach critique of it that are different than mine. But I can say that it's a film fascinated by all of the confusing, chaotic, contradictory ways we navigate tragedy. It's not a film cleanly about a single thing. It's the structure and narrative of a modern fairy tale serving as the backbone for a multifaceted meditation on pain and survival.

Give Weapons its due. I think Cregger's work deserves at least that much from us.