Let’s pick a fight right out of the gate: Modern television began on September 24, 1995. Like all beginnings, it went unnoticed, misattributed to other moments, and lost under the shadows of more visible and well known events. You could argue, instead, that modern television began on a different September the 24th, two years earlier. I think we’d mostly agree if you did. Though two years apart, we’re talking about the same writers, planting the same flag on two different hills. What were those hills? The X-Files’ first monster of the week episode, “Squeeze”, and the single season wonder Space: Above and Beyond. As for the writers? That would be Glen Morgan and James Wong.

“Wait,” you might be saying, “The X-Files was created by Chris Carter, not Glen Morgan and James Wong.”

You might even being thinking, “Am I supposed to know what Space: Above and Beyond is? What is Eric talking about?”

If you are, it’s fine. I warned you that I was picking a fight. After all, I never expected to be understood.

But I’ll do my best.

The problem with history is that nothing really begins or ends. Point to a spot on a timeline, say, “That’s the start of something,” and your annoying, pedantic friend can find a spot a little earlier and tell you all about how your choice couldn’t have happened without this earlier event. They’re right, of course. Nothing arises ex nihilo, no art is truly sui generis. Everything is connected. Still, you have to start a story somewhere.

On April 8th, 1990, a seismic event hit television. David Lynch and Mark Frost’s pilot for a strange, provocative murder mystery set in a small town in the Pacific Northwest landed on ABC and gained an instant cult following. It was one of those perfect water cooler conversation shows that, despite being intensely odd, had an all-too-brief chokehold on popular culture. Twin Peaks was unlike anything that television had seen, which is probably why the network forced changes that destroyed its popularity and chased its most vital creative force off for most of its second season. The era of Twin Peaks was short, but as impactful as anything the medium has seen.

It’s a moment you could call the birth of modern television. The shows that would chase the Twin Peaks high came fast and furious for much of the decade, and one of the very shows I called out only found a home because of that pursuit. Despite that, almost nothing on television since feels or works much like Peaks. Successors played around with quirky small towns, serialized mysteries, and the infusion of the paranormal into standard television formats, but it’s hard to argue that any of them were written, shot, or structured like what Lynch and Frost achieved. Twin Peaks, I’d argue, is not the beginning of modern television, but its precursor. None of the shows that would dominate genre culture would exist without Twin Peaks, but they owed more to its impact than its direct influence.

The success of Twin Peaks demonstrated the appetite audiences had for the weird. Horror and genre shows certainly weren’t unheard of in the medium’s history, but they tended to flare up, then recede into the mists without creating a movement. The Twilight Zone had its copycats, but by the time it was off the air, the rest followed soon after. Star Trek had a cult following that refused to die, but no great movement found purchase in its wake. By the 90s, some important things had changed. Rather than exclusively seeking shows that could appeal to all audiences, the emergence of cable television opened the door to shows that could be profitable serving just-large-enough niches. Peaks proved one of those niches existed. The question, then, wasn’t whether that niche was worth serving, but how.

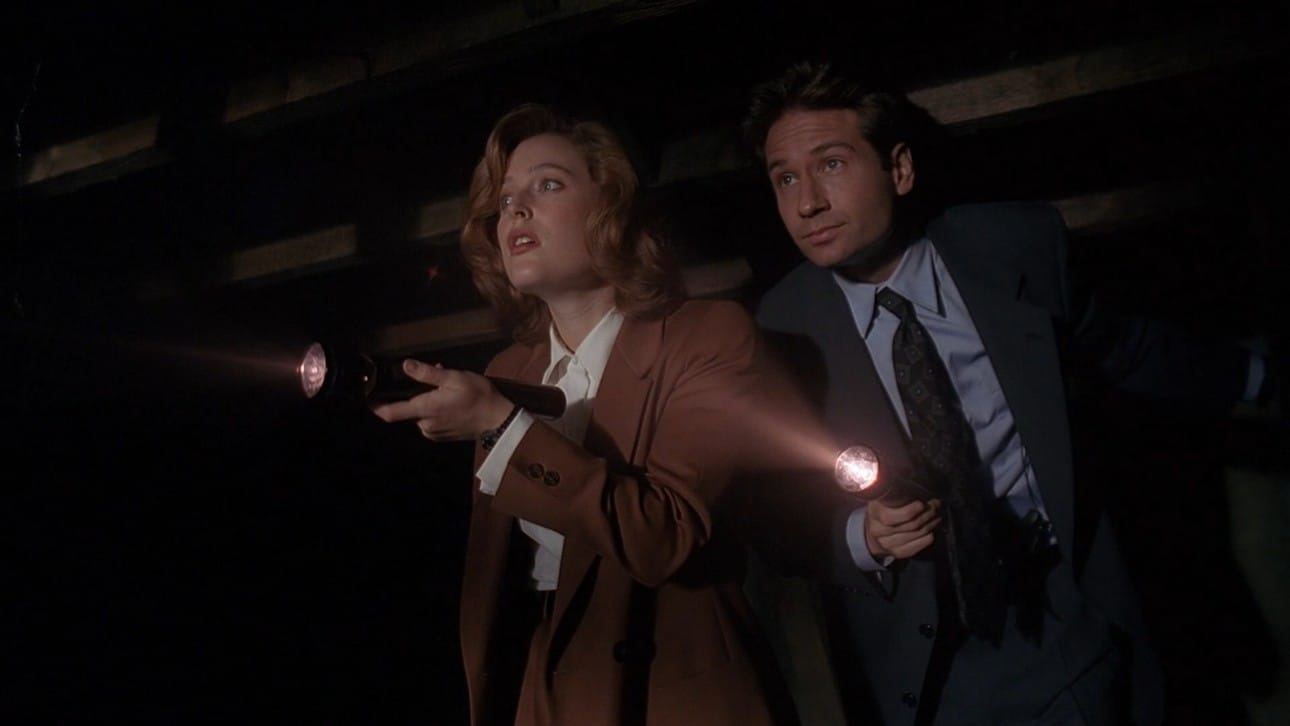

It was 1993’s The X-Files that finally cracked the code. Chris Carter’s alien conspiracy show was an early and critical mainstream success for the emerging Fox Network. Marrying an overarching “mytharc” focused on the government’s cover up of extraterrestrial life to stand-alone “monster of the week” shows was its masterstroke, keeping the idea of the connecting story that made Peaks so compelling while solving the problem of how to keep it going over a 22+ episodes a year. Carter’s first two episodes stayed tightly coupled to the first half of its format: aliens and conspiracies. It would be left to other writers to figure out how to make the rest work, and the first to step up to the plate would be writing partners Glen Morgan and James Wong, co-executive producers and the season’s most prolific contributors. They’d write six episodes that year, but it was their first, “Squeeze”, that instantly laid the foundation that would keep the show going long after Carter’s mytharc lost its way.

Born a continent and an ocean apart, Glen Morgan and James Wong became high school friends after their families both found their way to El Cajon, California. They enrolled at the School of Film and Television of Loyola Marymount University, graduating together in 1983. Their partnership would last over thirty years, stretching across nine television shows and four films. Though they’d come to be known for their genre work, their early career path went through crime procedurals, like 21 Jump Street and The Commish. It was one of their early bosses during that era, Peter Roth, who would woo them over to a show by a new and largely untested showrunner: Chris Carter. Despite some misgivings — Morgan and Wong intended to join a romantic comedy show called Moon Over Miami — Roth pushed them to watch the pilot and consider joining the team. He was, obviously, successful.

Knowing that aliens alone could not sustain an entire show, Carter set his writers’ room loose to clear the path ahead. Morgan and Wong’s idea for a liver-eating, hibernating serial killer named Eugene Tooms was The X-Files’ first attempt at what an alien-less episode could look like. That first attempt was all the show needed. “Squeeze” is, any way you could define it, the platonic ideal of an X-Files monster of the week episode. Merging classic horror tropes with the show’s signature wit — another trait that the pair are credited with establishing — “Squeeze” is scary, funny, a little gross, and perfectly paced. It’s rare for a show to find its formula so early, but the kind of episode that would define The X-Files remained basically unchanged from there.

Over the eleven episodes Morgan and Wong would write in the show’s first two seasons, they established a number of the elements considered foundational to The X-Files’ identity. Mulder’s love of cracking dry quips, known at the time as “Mulderisms”, are credited to the pair. They also created many of the show’s most famous side characters, including The Lone Gunmen and Assistant Director Skinner. They also brought Morgan’s brother Darrin into the mix during the second season, first as the man behind the mask of the iconic(?) Flukeman, then as writer of an episode that would establish the series’ ability to get way weirder and more comedic, first with “Humbug” then, later, “Clyde Bruckman’s Final Repose” and “Jose Chung’s From Outer Space”. To say The X-Files would be a vastly different show without Glen Morgan and James Wong would be a bit of an understatement, and they did most of it in those first two years.

Then, just like that, they were gone. They wrote their final (for then) episode, season 2’s “Die Hand Die Verletzt”, and departed to spin up their own new series. That show was 1995-96’s Space: Above and Beyond.

Science fiction television in 1995 came in one of two flavors: Star Trek, and Syndicated. A third flavor, Star Wars, had been tried with 1979’s Battlestar Galactica, then just as quickly abandoned; that kind of space opera was too expensive to produce on a television budget and schedule. Interesting things were happening at that moment in both Star Trek with Deep Space 9, and on syndication, with the low budget powerhouse Babylon 5. It was the latter that went all-in on a risky but critical innovation in the medium: heavy use of digital VFX for its space scenes. The problems Galactica ran into, balancing the need for big battles with budget limitations, finally had a solution.

The idea Morgan and Wong pitched to Fox probably wouldn’t have been possible without it. Where most televised sci-fi up to that point took place at a galactic scale, mixing dozens of alien races with high technology, Space: Above and Beyond was meant to be a more grounded and focused look at interstellar conflict. Inspired by the 1960s World War II series Combat!, Space was the tale of a sudden war between an Earth beginning to reach out into the stars, and the first alien race they encounter. The larger story was told through the eyes of a single Marine Corps squadron, the 58th “Wild Cards”, as they went on missions in space and on extraterrestrial worlds. There were signs of a conspiracy back on Earth — this was a show intended to be paired with The X-Files, after all — and other subplots, but the meat of the show was about the impact of war on a group of new recruits facing the traumas ahead of them.

The pilot aired on September 24th, 1995, and the show would struggle to find an audience from there as Fox reneged on the promise to the showrunners that Space would air side by side with the hit series they’d just left. Instead of having a home on Friday nights, Space mostly ran on Sundays, where it would be routinely delayed by football games running over time. While it gained a passionate cult following (of which I was a member, long live the 59th Ready Reserve!), it never broke through into wider pop culture acceptance. By the spring of 1996, the writing was on the wall, and Morgan and Wong brought the show to a brutal conclusion in its series finale, “…Tell Our Moms We Done Our Best”.

It’s here that I need to put my cards on the table. How can I argue that modern television traces crucial parts of its origins to a show that barely anyone saw, and that was cancelled without even having the brief moment in the sun that Lynch and Frost shared in the summer of 1990? Here’s why: there’s a difference between what was influential popularly, and what was influential to other writers. Some shows, like Lost, change television because studios see a market in creating more shows like it. Space was never that kind of show. There weren’t enough people in the audience to have that kind of impact, but while few of us were there in 1995 with our eyes and ears glued to the tube, there were future giants amongst us.

Morgan and Wong were writers’ writers, creators whose work primarily impacted their peers and successors. It was visible in their influence on the other writers on The X-Files, and in the years following Space: Above and Beyond, the bold choices the duo made writing their doomed passion project would bubble back to the surface in shows over the next decade.

Space: Above and Beyond forms one of my artistic core memories. It landed at a formative moment in my life, and along with some others like Babylon 5, redefined what was possible on television. It’s important to say this because I’ve spent all the years following its cancelation both obsessively following Morgan and Wong’s career, and hypersensitive to its influence on shows I’ve loved since. Is it possible I was, and am, so biased that I’m getting Boss Baby vibes from everything? It’s a question I’ve been wrestling with through this entire project.

I decided to return to Space this summer when I realized we were approaching its 30th anniversary. At first, this was for me alone. I’d seen some episodes more than once, and one particular episode, “The River of Stars”, is one of me and my mom’s Christmas traditions (along with Millennium’s “Midnight of the Century” written by Kay Reindl and Erin Maher — we’ll get back to that show soon). I hadn’t seen the whole show since it aired, though, and going back seemed like a fun idea. Things spiraled from that point. As I watched more of the show, and read things like Darren Mooney’s series recap project, thoughts about the under-appreciated impact Morgan and Wong had on modern television came back with a vengeance. The fingerprints of Space were on so many things, starting almost as soon as it had aired.

After the cancelation of Space, Morgan and Wong briefly returned to The X-Files before taking over the second season of its struggling sister show, Millennium. That season was another core memory for, airing during my freshman year of college. Even though the haze of depression that cloud my memories of that time, I clearly remembered almost every episode of that season. In fact, the second season of Millennium may have been even more impactful to me than Space. Its fearless mashup of apocalyptic doom, religious mysticism, and cosmic horror was unlike anything that had come before or, frankly, has come since. I said at the start of this that nothing really recaptured the feeling of Twin Peaks, but if anything came close, it was Morgan and Wong’s Millennium.

I decided I should rewatch that, too; a journey my wife decided to take with me. It was clear by then that I’d have to write about how important these writers were to me, how thoroughly they’d shaped my artistic sensibilities.

By the time we were deep into that season, though, my brain was reaching farther. This wasn’t just about my love for Morgan and Wong. My belief that they’d reshaped not just my views of the possibilities of television, but that of many of modern TV’s most important creators, was cementing. You can‘t take nostalgia out of the mix, but on this argument, I think the facts are with me.

The easy part of arguing that this dynamic duo’s work was instrumental in the birth of modern television is The X-Files itself. If you wanted to say that modern television truly begins with that show, I’d quibble, but not totally disagree. And if that were your argument, there’s no way to avoid that The X-Files wouldn’t be anything like what we remember without Morgan and Wong’s foundational contributions. This wasn’t limited to the story, either. In a conversation with Damon Lindelof, Chris Carter said:

I banked the names Morgan and Wong, who were so important to the success in the beginning, as they were writers Peter Roth had worked with at Stephen Cannell. They came not only with their stories to tell, but they actually gave us the way we would work. They brought in what we called “the board,” a bulletin board with 3 × 5 cards. That became the way The X-Files was plotted every single episode.

From The X-Files, we get clear, direct influences to some of our most vital shows of the late 90s and early 00s. Start with a series alum, Vince Gilligan, who’d go on to create one of the defining shows of what’s often called the Golden Age of Television in Breaking Bad. Gilligan’s work largely came after Morgan and Wong departed, but the influence Darrin had on him is clear — to the point where Gilligan cast Darrin Morgan in one of his earliest funny episodes, “Small Potatoes”. Gilligan also credits Morgan and Wong for their contributions to the show’s humor.

“Darin Morgan showed everybody that The X-Files could, indeed, be funny, but I tend to think that Glen Morgan and Jim Wong don’t get enough credit. Really, the first little whiffs of humor, as I recall, were in episodes written by them. They had some killer lines between Mulder and Scully in certain early episodes.”

The X-Files was also an influence on (and, in its too-long run, a cautionary tale for) Damon Lindelof when making Lost. Lindelof’s favorite episode? Darrin Morgan’s “Jose Chung’s From Outer Space”. The episode he thinks is scariest? Glen Morgan and James Wong’s season 4 classic “Home”. Just here, just in The X-Files, you have two of the most successful modern showrunners with roots not just in the series overall, but in Morgan and Wong’s work specifically.

The impact of Space: Above and Beyond takes a bit more work to trace, but its reverberations through television are clear. The most obvious impact can be seen first in the later seasons of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. While it’s difficult to find direct citations of Space’s influence, and it was certainly flirting with war themes since its inception, a rewatch of DS9 with Space in mind (a rewatch I just completed, in fact) shows a palpable inflection in their approach to the material in Space’s wake.

Season 5’s “…Nor Battle to the Strong”, one of the first episodes made in the season following Space’s cancellation, is the kind of on-the-ground war story Morgan and Wong revived in their work. There are also moments of the score in those later seasons obviously influenced by Shirley Walker’s incredible score for Space. Is it fair to claim influence without quotes from the writers admitting it? I don’t know, but they also never admitted that DS9’s entire concept was stolen from J. Michael Straczynski’s Babylon 5 pitch to Paramount.

From Deep Space Nine we can then follow the work of Ronald D. Moore, who’d go on to create the gritty, grounded war story remake of Battlestar Galactica, a show you simply cannot watch and miss Space’s influence. I am, again, unable to prove this with quotes, but let’s do this: compare the EVA sequence in “The River of Stars”, which has a moment of a character, magnetically stuck to the hull of a ship, upside down as he looks out into space, to a very similar moment from the Ron Moore co-written Star Trek film First Contact. Or take Space’s “The Angriest Angel”, about a traumatized pilot facing off against a dangerous enemy ace, then look at Battlestar’s “Scar”, about, y’know, a traumatized pilot facing off against a dangerous enemy ace. There are also the clear echoes of “The Dark Side of the Sun” in “Maelstrom”, and of the biomechanical interior of the Chig ship in “Hostile Visit” in the similar aesthetics of the Cylon Raider in “You Can’t Go Home Again”. Interestingly, Battlestar’s composer, Bear McCreary, cites Space and Batman: The Animated Series composer Shirley Walker as a major musical influence.

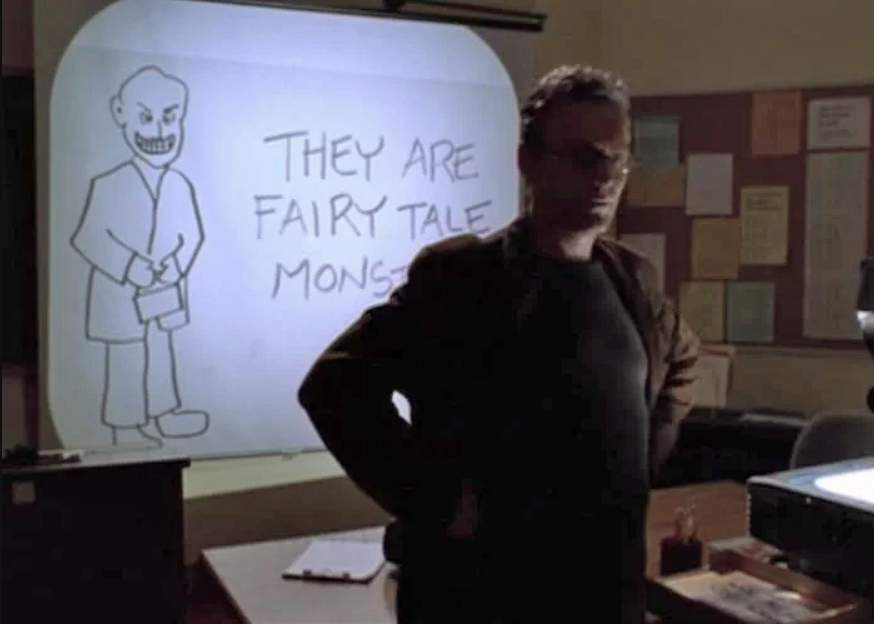

Space’s influence goes beyond the obvious. One of Morgan and Wong’s boldest works is “Who Monitors the Birds?”, a nearly dialogue-free episode following a character trapped in hostile territory as he flashes back to his early life in an indoctrination center. Experimental and ahead of its time, it’s an episode cited by Joss Whedon as a primary influence on Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s season 4 “Hush”. There’s even a silent slide show in “Who Monitors the Birds?” referenced in the overhead projector scene in "Hush". Whedon loved the episode so much that he cast its central star, Rodney Rowland, in an episode of Angel. Oh, and side note: VFX supervisor Glen Campbell and his Area 51 Studios, whose first major work was Space: Above and Beyond, worked on the first season of Buffy.

Millennium season 2’s influence is more diffuse. A risky, experimental season of television, it pushed the show beyond its serial killer roots and into a place of both personal and global apocalypse. The second season’s arch, mystical approach to its handful of returns the show’s original serial killer premise can be felt in things like Bryan Fuller’s Hannibal and Nic Pizzolatto’s True Detective. What do I mean by that? Take a look at something like “The Mikado” or “A Room With No View”. There’s also a nearly 10-minute sequence in the season finale, of a character breaking down set to Patti Smith’s “Land”, that has no precedent. It feels as much like a precursor to some of what Twin Peaks: The Return would do as Twin Peaks feels to Millennium itself.

Once you start looking, you can’t stop finding things in Morgan and Wong’s mid-90s work that influenced or presaged what television would become as we entered the Golden Age to come.

Maybe you’re not convinced. Perhaps this really is seeing the echoes of something revolutionary for me, personally, in places actually untouched by it. If that’s so, I accept it, because no matter how strong an argument I make, we find ourselves back at the opening of this piece: how do you ever know, for certain, when something began? Television in the 90s was a broad and deep river, with creators exploring the new space given to them by cable (both basic and premium) and the fragmenting audiences that forced shows to narrow in on who would watch them. No artist has a singular influence, either. Every show, every writer I mentioned, took cues from dozens of places.

I believe, though, that there are sometimes artists that serve as lenses, focusing diffuse light into a pinpoint beam. They did not do all of the work themselves, but found their own synthesis of the eddies and currents of their moment, and whose work catalyzes those forces for others. That, to me, is the impact of Glen Morgan and James Wong. Their work fused the well-honed structure of 1980s dramas with the weirdo curveballs of artistic experimentation finally possible in the medium in a way that lit the path ahead for others. In establishing the identity of The X-Files, they left a legacy through one of the 90s most defining works. With Space: Above and Beyond, they made television science fiction grounded, tragic, and tangible without losing the adventurous fun that a series needs. And their brief run on Millennium was an occult explosion, a refusal to boil the supernatural down to something understandable in a format that focused Twin Peaks' lessons into a structure that people without Lynch’s singular vision could replicate.

There is so much to their work that now feels almost standard: their balance of darkness and humor, their clever use of musical juxtaposition, their willingness to break formal ground in single, experimental episodes. The things we’d consider “modern television” were only just emerging into the light in the mid 1990s. Other shows, other creators, played with many of them. It was Morgan and Wong, though, who seemed uniquely positioned to bring them all together, and in a way that audiences could be taught to understand.

Did Morgan and Wong invent modern television? Who really invents anything in art? Without a doubt, though, they exemplified it. Whether it was truly the beginning or not, to return to the work of Glen Morgan and James Wong is to see, in the clearest possible light, that the future of television had finally arrived.